To Curb Gang Violence in Haiti, Break with Politics as Usual By Louis-Henri MARS 18 Avril 2023 News I know...

Lakou Lapè – Peacebuilding in Haiti

Louis-Henri Mars has seen it happen too many times: “For many kids in Haiti, violence is the norm. Let’s take ‘Jean’ growing up in a slum like Martissant. At age four or five he joins a kiddie gang, building homemade weapons with small rocks as bullets. His heroes are gang leaders like Barbecue and Ti Lapli. His mom, a single parent with four other kids, doesn’t have the money to send them to school. Jean makes pocket change by doing errands for the gangs—buying cigarettes, fetching their guns.

“As Jean gets older, the gang gives him his own pistol, and he becomes an apprentice soldier. Jean kills someone from another gang, gaining respect and landing him promotion as a full-fledged soldier. If he shows loyalty to the gang’s boss, shows leadership and is ruthless, the gang might put him in charge of a neighborhood. He earns money— kidnapping, gun running, extorting taxes from market women and tap tap drivers. The kid now becomes his family’s breadwinner. What can his mom say? Financially, it’s a good arrangement for her. She, too, has respect. After all, she is Jean’s mom. Jean has no schooling, but he’s now a boss with power, money, fine clothes, and a couple of girlfriends.”

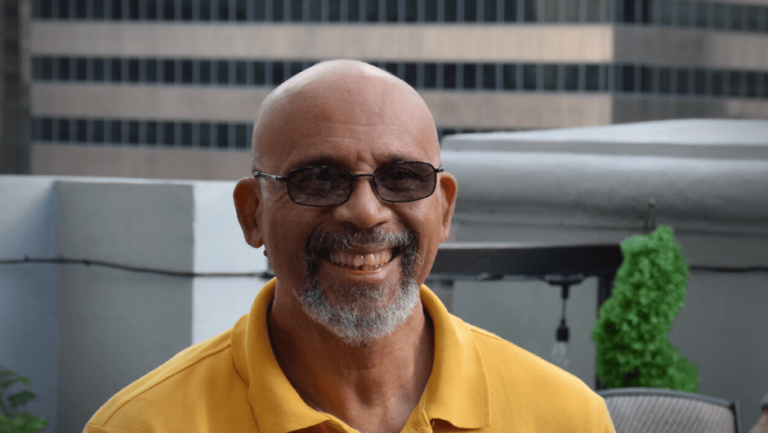

Louis-Henri, the executive director of IAF grantee Lakou Lapè (which means “courtyard of peace” in Haitian Creole), has dedicated his career to giving young people like Jean the option of a different life path. Lakou Lapè promotes peaceful dialogue and conflict transformation in violence-prone sections of Port-au-Prince, promoting young leaders as a counterweight to the armed gangs that dominate those areas.

Louis-Henri has focused on giving adolescents and youth surrounded by gang activity viable alternatives to conflict and crime. Without these options, any break in gang activity just creates an opening for the next generation of gang leaders to take their place. At times, entire gangs follow their leaders out of crime and violence, inspired by the teachings of Lakou Lapè and other organizations. However, sometimes within hours, a new generation of young people reach the top of the gang world.

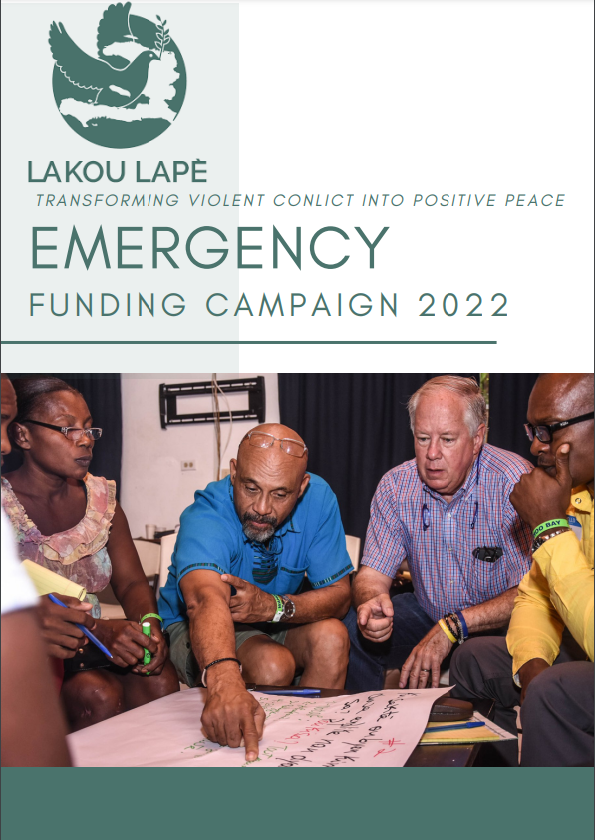

With its IAF grant, Lakou Lapè has brought together young people, including young people from areas where gangs are at war with each other, to create a network of 85 youth peace builders. The organization has trained them to transform conflict by identifying a conflict’s root causes, listening, dialoguing, and building and restoring relationships.

Lakou Lapè also emphasizes challenging injustices and understanding and addressing the trauma most young people have experienced. Louis-Henri says, “If someone throws a rock at me, rather than filling the individual with bullets, these techniques teach me to analyze, ‘Why would a person do that? What can I do to break the cycle?’”

Lakou Lapè provides its peace builders with vocational, professional, and small business development training. It also connects them with people from different sectors of society: business owners, civil society organizations, and political actors. Some business people have partnered with these young people to develop micro-enterprises. Each young person the network trains has a multiplier effect: 15 young dialogue facilitators went on to train an additional 500 youth in the Port-au-Prince neighborhoods of Cite Soleil, Saint Martin, and Bel Air.

“How the youth react to our work gives me hope,” says Louis-Henri. He often hears from young people who found their training life-changing. “Now we have 360 youth in Cite Soleil and 140 in Bel Air who are all fired up to work on peace in their neighborhoods. We have to keep investing in young people in a position to help guide their neighborhoods out of violence.”

For the first decade and a half of his career, Louis-Henri focused on building a manufacturing company that assembled electronics and leather apparel. The military coup d’ etat in 1991 sparked his concern for the state of Haiti. Everything shut down due to the embargo and ensuing instability. Angry citizens took to the streets, throwing rocks, setting tires on fire, and looting stores. “There is something deeply wrong,” thought Louis-Henri. “I wanted to understand what was behind the recurring conflicts and rage. I realized that the country’s economic and social benefits were out of reach for the vast majority of Haitians. People expressed their frustration through violence.”

Louis-Henri slowly started learning about leadership development and peace building as well as mediating local disputes: “I focused on developing leaders anchored in the spirit of God who could transform Haiti.”

Between 2007 and 2011, he facilitated dialogues between the business sector, grassroots organizations, and people from gang-dominated areas in partnership with The Glencree Center for Peace and Reconciliation of Dublin, and Concern Worldwide. He traveled twice to Ireland and witnessed their peace process. After experiencing how deep dialogue can build community between people of different social origins, he helped establish Lakou Lapè in 2013.

With his professional training and resources, Louis-Henri could live and work almost anywhere. What keeps him so committed to Haiti, where he regularly faces risk and loss? “When I travel, I miss my home after a week. I have a sense of mission and agency,” he says. His family history also keeps him anchored to the island, with his grandfather serving as a minister in the Haitian government and an ambassador and his father serving as Haiti’s first psychiatrist: “Like my family members, I want to give back and achieve something positive during my lifetime.”

Conversations with Louis-Henri often start with, “Can you hear the shooting?” or “I’m thankful I’m safe. A friend was kidnapped a month ago…” Despite the tension and danger, Louis-Henri draws inspiration from his vision for what Haiti would be like if its communities were peaceful: “If we had peace, businesses would invest, and Haitians could walk down the street and lead a normal life. I could go anywhere without fear of getting shot or kidnapped.” As it is, “residents are cowering in their homes. Hotels have closed. Protesters have blocked roads. Gas is scarce. Inflation is rampant. People are hungry and frustrated. If I go downtown, I have to let my people know and travel in a well-marked car,” he says.

In a workshop Lakou Lapè held back in December 2021 with 50 peace builders, implementers, and funders, participants were struck by the lack of overall impact of peacebuilding, humanitarianism, and development as a whole in Haiti. In Louis-Henri’s words, “The need to optimize our collective impact has come to the forefront of our thinking. Many actors are doing wonderful work that is disconnected with what others are doing. How can we help coordinate, communicate, build continuity, share data, strategize together?” The organization is actively exploring how to play that articulating role and systematically involve local communities, non-governmental organizations, businesses, politicians and government officials, the media, and international organizations in analyzing issues and searching for solutions together.

Louis-Henri envisions these national cross-sector dialogues as bottom-up, ongoing, and independent from the limits of project-based funding: “For things to change, all parts of society need to be involved. We have to address the root causes—hunger, lack of education, unemployment, discrimination, economic inequality, poor governance, corruption. Otherwise, the cycles of violence continue.”

To Curb Gang Violence in Haiti, Break with Politics as Usual By Louis-Henri MARS 18 Avril 2023 News I know...

Fostering Peace in Port-Au-Prince: An Interview with Louis-Henri Mars By Carolina Cardona and Rebecca Nelson 21 September 2022 News Louis-Henri...

To Curb Gang Violence in Haiti, Break with Politics as Usual By Louis-Henri MARS 18 Avril 2023 News I know someone who was once the leader of the Grand Ravine gang in the south of Port-au-Prince. Around the time he became the gang’s leader, a United Nations mission in Haiti was moving to confront and dismantle gangs. In 2006, Haitian officials, with support from a U.N. disarmament program,...

Fostering Peace in Port-Au-Prince: An Interview with Louis-Henri Mars By Carolina Cardona and Rebecca Nelson 21 September 2022 News Louis-Henri Mars has seen it happen too many times: “For many kids in Haiti, violence is the norm. Let’s take ‘Jean’ growing up in a slum like Martissant. At age four or five he joins a kiddie gang, building homemade weapons with small rocks as bullets. His heroes are...